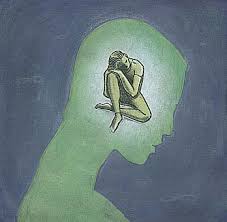

Could Body Dysmorphia Disorder be described as a degree of Disturbia – a mental disturbance? Disturbia syndrome is a depiction of the silent epidemic that is not often spoken about nor prepared patients for the possibility of happening. The surgery has a tremendous effect on patients: emotionally, physically, and mentally. Unfortunately, after bariatric surgery, most patients often falsely perceive their size and what they look like. Some fail to recognize the significant reduction in their weight, others consistently obsess in front of the mirror, staring at their perceived flaws, and others continue to buy and wear clothes that fit their former size. Patients’ misjudgment of actual appearance can lead to lowered self-esteem or even depression. This blog aims to reach broader awareness about this issue and implement the basic steps in education that practical tools for pre-surgical bariatric patients can apply immediately.

What Is Body Dysmorphia?

The term “body dysmorphic disorder” (BDD) refers to a condition in which a person obsesses about an “imagined” flaw in their appearance. The fixation is linked to numerous time-consuming activities, such as persistent comparing or mirror staring (Veale, 2004).

Why Does It Occur Among Bariatric Patients?

It takes time following surgery for the brain to align with the body. For example, a person who has had weight reduction surgery and has lost weight rapidly often develops an unrealistic perception of an attainable body (Munoz et al., 2010).

Furthermore, after years of obesity concerns, unsuccessful diets, and unfavorable self-perceptions, for a post-bariatric surgery patient weight, it is still challenging to modify such a deeply ingrained mentality (Gilmartin, 2013). Patients often see themselves as much more significant than they are; although the body weight scale shows a reduction, it may be difficult for them to notice a change in their physique.

Coping With Body Dysmorphia Post-Bariatric Surgery

Find social support. While body dysmorphia is not generally discussed, many weight reduction surgery patients have it. Bonding with other patients in similar situations as patients share personal experiences from bariatric surgery, engaging in deeply sensitive discussions relating to adjusting to establishing new relationships and sustaining old relationships after bariatric surgery, and swapping clothes with fellows from bariatric support groups as a celebratory moment (Marques et al., 2011).

Seek assistance. Therapists, bariatric dietitians, and other mental health professionals may assist with cognition, anxiety, and self-perception, from altering your connection with food to cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). In addition, post-surgery care providers should be mindful of the patient’s level of sensitivity, create a non-judgmental environment of weight regain, and discuss other mental health concerns like suicidal ideation (Gilmartin, 2013).

Avoid comparison (Hildebrandt et al., 2008). Everyone’s weight reduction journey is varied on the patient’s genetics and their biochemistry composition; thus, everyone will see different outcomes in varying amounts of time. Spend time with positive individuals who bring you up and create connections in and beyond the weight loss community. Learn to accept compliments without questioning the individual’s motive behind the statement made, become optimistic about your body type and the “small wins” after bariatric surgery, and try positive mirror self-talk. Body dissatisfaction among post-surgery patients can be expected. Give yourself time to love yourself and your body and surround yourself with supportive people who can help you perceive your body more accurately than you do.

In conclusion, “Disturbia” is a mental disturbance; not every bariatric patient will experience body dysmorphic disorder. Stigmatization is prevalent in the bariatric surgery community among the general population. No one wants to be stigmatized as emotionally unstable and undisciplined. However, it is imperative to assist bariatric patients in reaching or beginning the understanding of how the brain is programmed to view the human body in its previous state. Mental Health and Emotional Health history is accumulated from childhood years and significant relationships throughout their adulthood years that have shaped the patients’ perception of self and emotionally. Bariatric patients have various options like attending preoperative/ postoperative support groups. Another option is visiting a mental health counselor to assist in organizing negative and positive emotions constructively to prevent the development of self-destructive habits. Bariatric patients must remember that bariatric surgery is one of the necessary tools to save lives and restore quality well-being to promote vitality. Body Dysmorphia Disorder can be treated and often cured with the right interdisciplinary team, patient cooperation, and social support system.

References:

Gilmartin J. (2013). Body image concerns amongst massive weight loss patients. Journal of clinical nursing, 22(9-10), 1299–1309. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.12031

Hildebrandt, T., Shiovitz, R., Alfano, L., & Greif, R. (2008). Defining body deception and its role in peer – based social comparison theories of body dissatisfaction. Body image, 5(3), 299–306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2008.04.007

Marques, L., Weingarden, H. M., LeBlanc, N. J., Siev, J., & Wilhelm, S. (2011). The relationship between perceived social support and severity of body dysmorphic disorder symptoms: the role of gender. Revista brasileira de psiquiatria (Sao Paulo, Brazil: 1999), 33(3), 238–244. https://doi.org/10.1590/s1516-44462011000300006

Munoz, D., Chen, E. Y., Fischer, S., Sanchez-Johnsen, L., Roherig, M., Dymek-Valentine, M., Alverdy, J. C., & Le Grange, D. (2010). Changes in desired body shape after bariatric surgery. Eating disorders, 18(4), 347–354. https://doi.org/10.1080/10640266.2010.490126

Veale, D. (2004). Body dysmorphic disorder. Postgraduate Medical Journal, 80(940), 67-71. https://doi.org/10.1136/pmj.2003.015289